Auditors will never be independent

October 18, 2016

|

Michael K. Shaub

I am approaching my 40th anniversary of entering the accounting profession. Since my first introduction to the professional world, I have been told that auditors must be independent in fact and in appearance. I have only one problem with that statement. It’s not true.

Max Bazerman and his colleagues have made the case that auditors are incapable psychologically of being independent. I largely agree with his arguments, but that is not the point of this essay. For purposes of the discussion here, I am assuming that I am incorrect and that it is possible for auditors to be independent in mind, or in mental attitude. Even granting the premise, I am saying that they never will be.

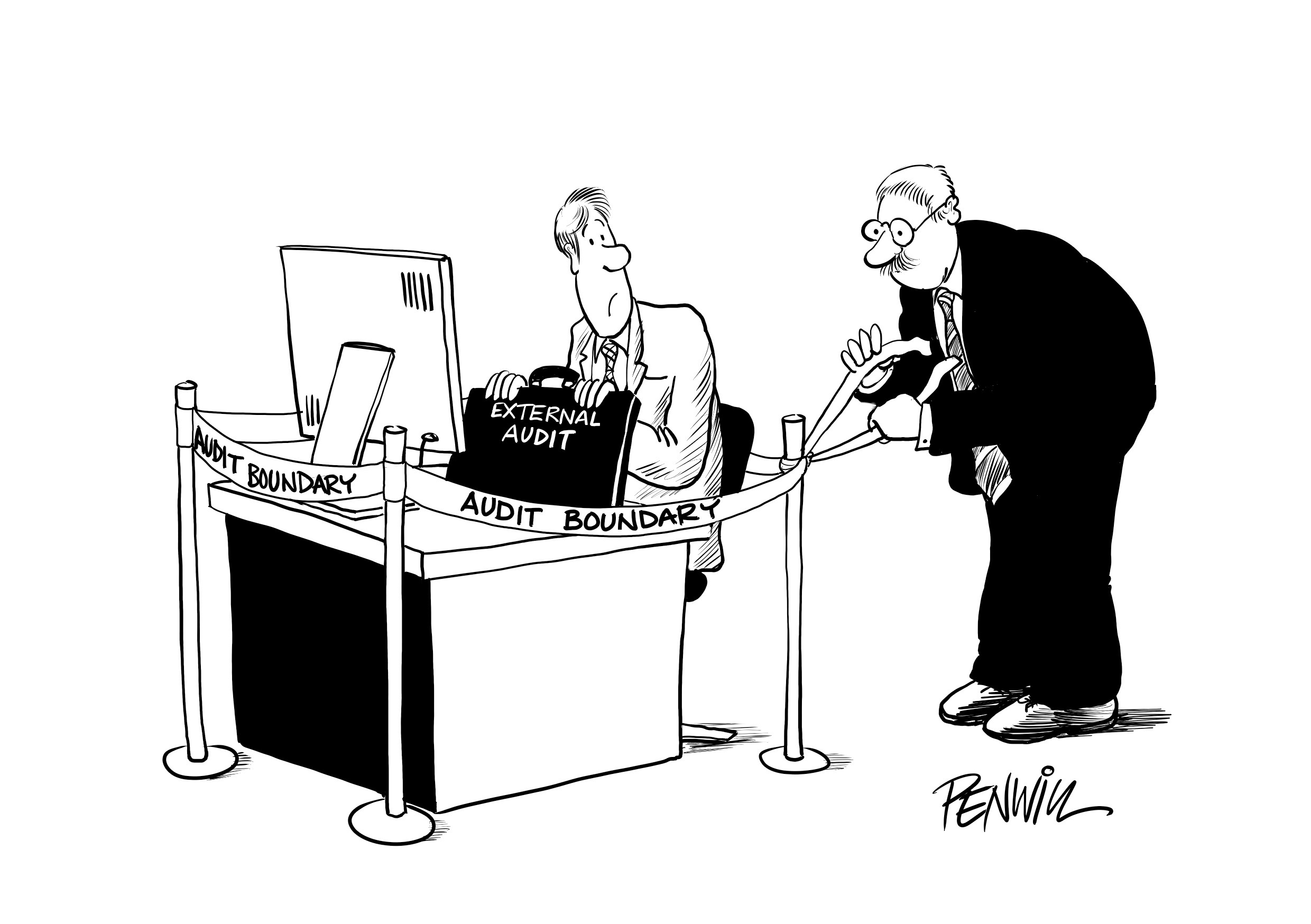

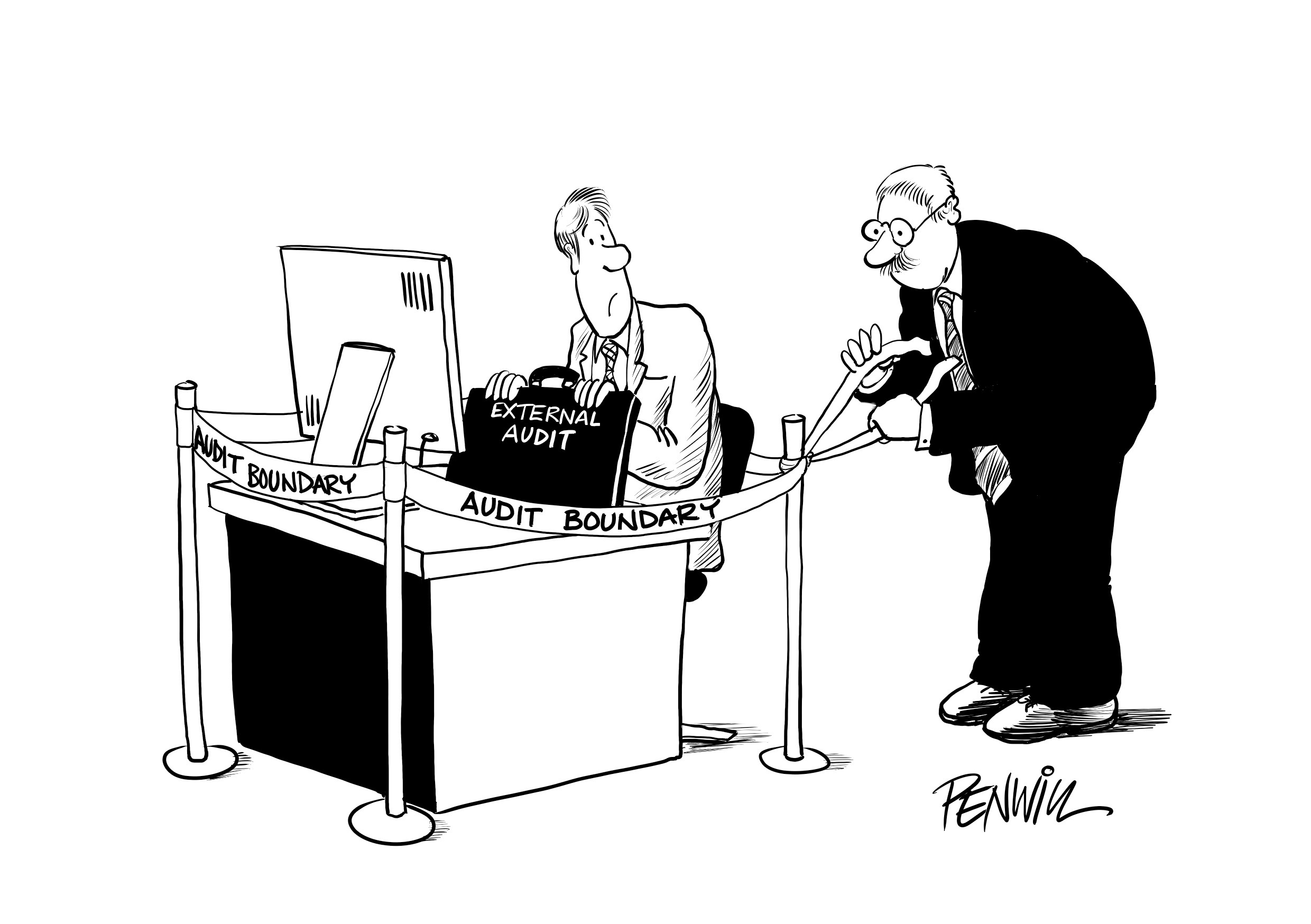

Independent Audit, Ltd.

There are several reasons for that. First, they don’t want to. I can easily point to egregious violations that have brought recent sanctions, such as the EY partner who had a relationship with a public company’s chief accounting officer, or the “relationship partner” who wined, dined and wooed the family of a CFO who was unhappy with the firm. But the truth is, auditors rationally want their clients to be happy. If you are going to drive through rush-hour traffic every day or work busy season hours, it is no fun to arrive at a grumpy client who wishes you would leave. My students are well prepared to be charming and to keep clients happy, because their short-term happiness is tied to the client’s.

Second, the accounting firm doesn’t want them to. That is why firms have appointed “relationship partners” in the first place. KPMG thought that was a good role for Scott London, the LA audit partner who went to prison for passing on inside information about audit clients such as Skechers to a golfing buddy. London was the “relationship partner” at Skechers for five years between his two terms as engagement partner, because he was forced to sit out by Sarbanes-Oxley audit partner rotation rules. Of course, accounting firms don’t want auditors breaking independence rules such as owning client stock, mistakes that can be very expensive for the firm. But empathy for clients is a common theme that has been consistent across the decades as I have taught – not that much different in tone from my days as an auditor. And that empathy is an explicit part of client retention strategies.

In addition, clients don’t want them to. While management may not particularly want auditors around, it makes sense to build a trust relationship with the auditor. Auditors have to trust clients in any circumstance, because they cannot audit everything. A skeptical auditor is potentially more expensive for an honest client, and can be downright dangerous for a dishonest client management. So it is natural to want to make auditors feel like part of the team, to make them comfortable with rooting for the company. Occasionally an audit committee member may try to restrain this tendency, but it is rare.

Finally, the AICPA doesn’t want them to. In particular, the unwillingness of the primary body driving policy in the public accounting profession to consider alternate reporting models protects the current model. And the current model, even with a few recent tweaks, is a “one size fits all” seal of approval that contains no real information. If you meet the minimum standard, you are fine. The recent introduction of “critical audit matters” into the PCAOB opinion has come only after years of wrangling and minimizing the impact of these paragraphs, under the guise of protecting the profession from liability. In addition, being a “trusted advisor” to clients is central to the AICPA’s vision for the future, known as CPA Horizons 2025. “Trusted business advisor” was a term trademarked by Arthur Andersen. Whatever else can be said about Arthur Andersen, their goal was to be a “one stop shop” for their clients.

But the AICPA will not allow alternative (higher quality) forms of opinions to compete in the marketplace, opinions that would provide partial guarantees to shareholders. Allowing alternative opinions would create space for firms to charge a premium over the cost of a regular audit if they are willing to assume the risk and do high-quality audits. Significant evidence exists that people will pay a premium for certainty as opposed to “reasonable assurance.” The presence of gold, silver and bronze opinions would also allow users to differentiate the level of assurance being provided by the audit, introducing legal protections for those offering the lower quality audits because clients passed on the “gold” audit. And perhaps most importantly for the marketplace, it would stimulate the development of “audit only” firms who could compete with the large public accounting firms, but without the pressure of keeping clients happy.

There are other structural ways of strengthening independence that have been suggested over the years, most dismissed out of hand by the AICPA. Perhaps the best one is for corporations themselves to buy insurance on their financial statements, and for the insurers to hire the financial statement auditors. This would mean the auditors would have a client (the insurer) who is deeply interested in the quality of the audit because, unlike audit clients today, their interests would be aligned with those of an auditor interested in protecting the public.

Today, instead, we repeatedly see the interests of young auditors quickly aligned with those of their clients. There is nothing structural in the profession, or in the accounting firm, or with the client that prevents that emotional attachment that comes with trying to keep the client happy. Professional skepticism is unnatural in the client-pleasing environment that exists in the firms, and it is irrational to expect it to develop unless something intentional is done.

For the last 10 years, I have had the privilege of teaching ½ to 1 percent of all the people sitting for the CPA exam in the United States each year. I am well aware that unless my students equip themselves to recognize the danger signs of being emotionally attached to clients, they have little chance of being independent in mind. Fear of lawsuits is insufficient to accomplish that, except for a brief time in a particular geographic location after a scandal.

Like most people, my students are far too trusting of successful people. So we wrestle in both Auditing and Accounting Ethics courses to help them calibrate an appropriate level of skepticism. Watching them do that really helps me not to be cynical, and it gives me hope that we can change the profession, and not wait for the top-down intervention that is inevitable when there is another crisis.

But after 40 years, I’ve come to this conclusion: Auditors will never be independent.

Auditors will never be independent.